THE WEBB LAMP CO LTD AND ITS SEWER GAS EXTRACTOR AND DESTRUCTOR LAMP

And no -

At the top of the hill on the Strand pavement, next to the 'Coal Hole' pub is a second more conventional gas lamp, which once carried stained glass advertisements for the 'Savoy Theatre' on its lantern.

These lamps, then both of the Webb type, were installed in 1897 and paid for by the newly built rival hotels on either side of Carting lane, the Savoy (1889) -

Both were deadly rivals for London's most luxurious hotel, and any hint of a sewer smell from the Carting Lane sewer would be bad for business. In more open, low rise, suburban locations the sewer would have been ventilated by a tall 'Stink Pipe', but both hotels were 12 stories or more tall and close together, and any stink pipe would merely have discharged the noxious smell level with the windows of both their bedrooms.

This was exactly the situation that Webb's Patent Sewer Gas Extractor and Destructor was designed for. Presumably the two lamps survival may be because they were privately owned – clearly the Coal Hole lamp carrying the Savoy Theatre advertisement was the one paid for by the Savoy hotel, and the surviving lamp the one paid for by the Hotel Cecil (demolished 1930).

Joseph Edmund Webb (1862-

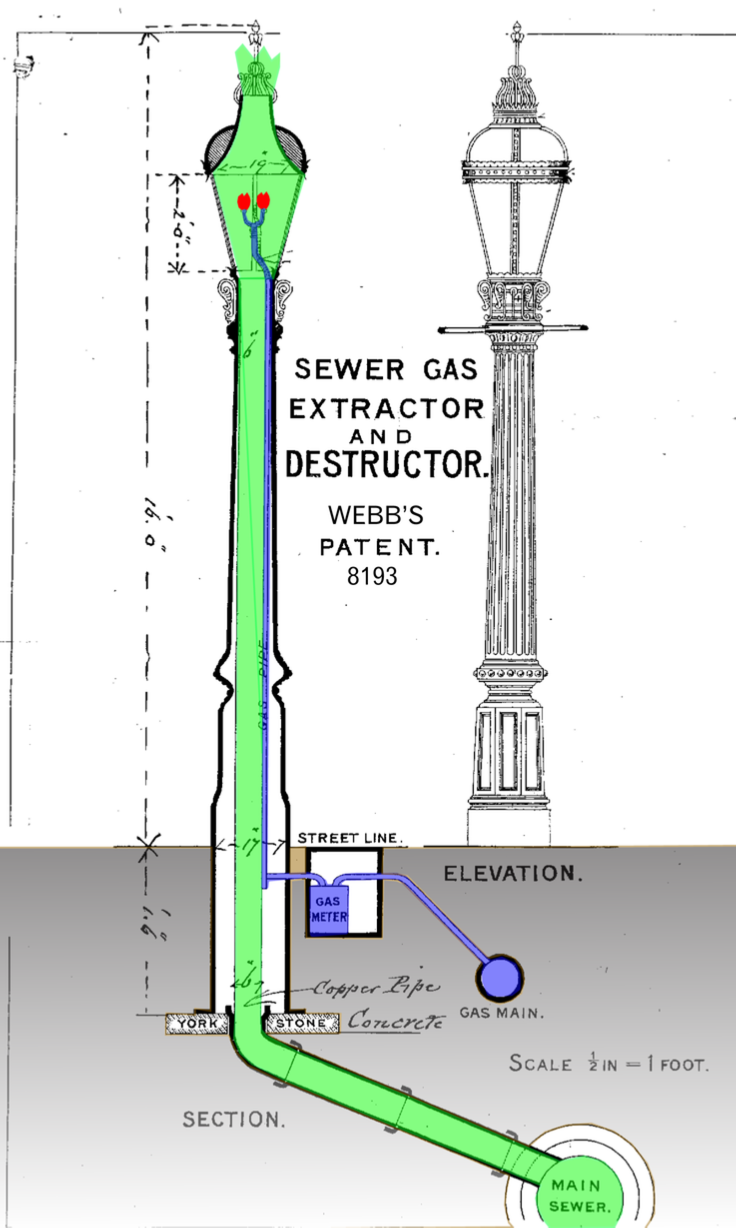

His initial design is summarised in the Patent thus:

'The object of the invention is to extract the obnoxious gases and vapour collected or generated from a sewer and at the same time to effectually destroy all germs and noxious qualities prior to their passing into the atmosphere. For this purpose I propose to utilise ordinary lighting gas which may at the same time be used for street or other lighting purposes'

The lantern and pillar were hermetically sealed, with a conventional town gas lamp burner. Sewer gas was drawn up the column from the sewer by convection and passed through the burner. A small by-

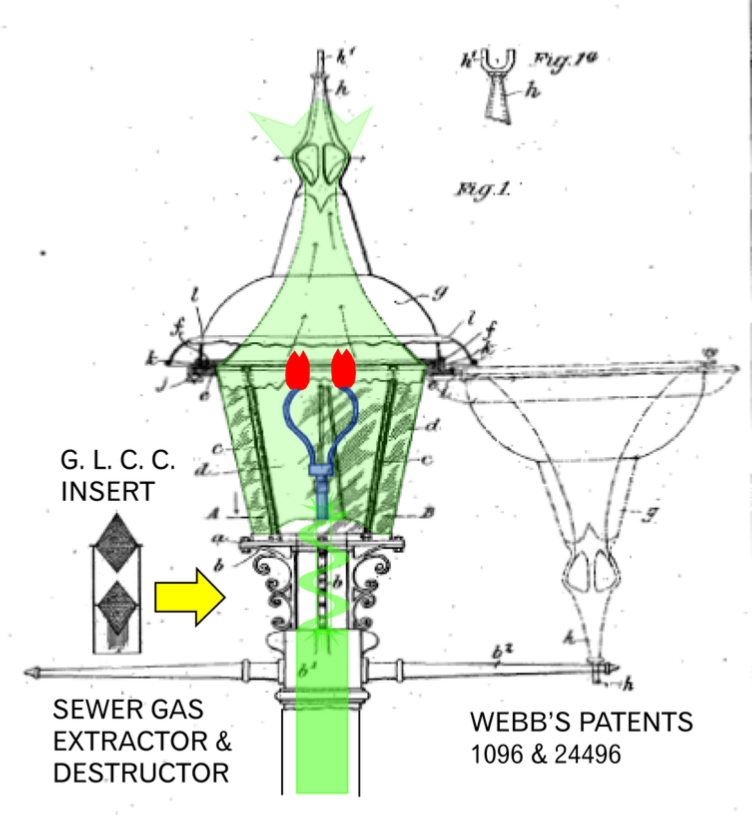

A subsequent patent modified this design by introducing a capsule below the lantern containing a series of copper gauze filters to prevent explosive flash-

However the final design, which was the one installed in Carter Lane, got rid of the hermetically sealed lantern, and had an open gap between the top of the column and the bottom of the lantern (where the GLCC capsule had been placed), which presumably mitigated the chance of a flash-

In 1896, when the company that would eventually become the Webb Lamp Company Limited of the Cairo works, 42 Legge Street, Birmingham was set up, with Joseph Edmund Webb (1862-

1894 W Deakin & Co, Sanitary Works, Guest Street, Hockley. 'Our Mr J E Webb the inventor'

1895 Joseph Edmund Webb 223 New John Street West, Hockley. Builder & Contractor

1896 Joseph Edmund Webb Sanitary Depot, Gas Street, Birmingham. Sanitary Engineer

1901 Joseph Edmund Webb 11 Poultry, City of London. Engineer.

Unfortunately all the records of the company were lost in a fire in 1925, so no definitive list exists of locations, but known locations for one or more lamps were:

Abergavenny

Alton

Barcelona

Barry

Bournemouth

Brighton

Canada

Cardiff

Dorchester

Douglas

Durham

Edmonton

Exmouth

Falmouth

Grantham

Hampstead

Harrogate

Hereford

India

Isleworth

Leicester

London County Council

Malvern

Morpeth

Neath

Newcastle

Oldbury

Paris

Pembroke

Poole

Portsmouth

Rippon

Seaton

Sheffield

Shoreditch

Singapore

Southampton

Southend on Sea

St Pancras

Stockton on Tees

Stourbridge

Tettenhall

Tottenham

West Bromwich

Westminster

Weymouth

Whitley Bay

Whitley Bay

Winchester

Wrexham

and the mortuaries of the London Hospital and Wolverhampton Hospital.

Webb Lamps were popular in hilly towns such as Sheffield where gas pockets might accumulate; in high rise urban areas where stink pipes would not rise above the buildings such as Carter Lane; and in cathedral cities such as Durham, Winchester and Rippon. The company’s advertising pointed out that independent tests had showed that the lamps used no more gas than ordinary lamps but that the illumination was increased at least 5% ‘newspaper type being read at 50 yards’, so you got three benefits (ventilation, sterilisation and more light) for no extra running cost.

In 1907 the company claimed that its lamps were ventilating 30,000 miles of sewer; however the market was ultimately limited, and was destroyed by changes in the Public Health Act (and the death of the 'Miasma' theory) which required building drainage systems to be individually vented at roof level by a 'ventilated stack', thus providing widely distributed sewer ventilation and removing the necessity to individually ventilate specific trouble spots. In addition, the rise of electric street lighting saw the replacement of gas lamps generally. By 1911 the company had diversified into manufacturing the 'Galvo Electryne' fire extinguisher, filled with carbon tetrachloride, and progressively this became their main product. Indeed the Webb Lamp Company's name is forever preserved in a landmark legal case which is still quoted as Chancery case law when they were sued by the American Pyrene Co (who made a similar extinguisher) in 1920 for patent infringement during WWI. They claimed as government contractors they were exempt from patent law.

The Webb Lamp Co Ltd maintained its offices in central London at 11 Poultry till 1918 and King Street St James till 1923. Joseph Edmund Webb died in 1936 having retired to a substantial house in in Brighton and leaving £11,891 (£771,000 in 2016) -

The lamp now on the site of the Webb lamp bought by the Savoy Hotel

Webb’s patent drawing showing the separate town gas supply to the burners

Webb’s subsequent patent drawing showing the open base of the lantern and the hinging cowl