MODERN ACCOUNTS OF LANDING ON CAPE HORN ISLAND

The next person to land on Cape Horn Island was 260 years later when Captain (later Admiral) Robert FitzRoy of the Beagle was employed by the British Admiralty to chart the treacherous waters around Tierra del Fuego.

As these accounts show, both landing and making progress on the island are extremely difficult and challenging.

Narrative of the Surveying Voyages of the ‘Adventure’ and ‘Beagle’ 1826 – 1836 describing their examination of the southern shores of South America. Philip Parker-

FitzRoy – 19th April 1830:

I afterwards went in a boat to Horn Island, to ascertain the nature of the landing, and whether it was practicable to carry any instruments to the summit of the Cape. Many places were found where a boat might land; and more than one spot where she could be hauled ashore so that taking instruments to the summit did not seem likely to be a very difficult task. As the weather continued favourable I returned on board that night, and the next morning (19th) arranged for a visit to Cape Horn; a memorial having been previously prepared, and securely enclosed in a stone jar.

After taking observations at noon for latitude, we set out, carrying five day’s provisions, a good chronometer, and other instruments. We landed before dark, hauled our boat up in safety on the north-

At daybreak we commended our walk across the island, each carrying his load; and by the time the sun was high enough for observing, were near the summit, and exactly in its meridian; so we stopped while I took two sets of sights and a round of angles. Soon afterwards we reached the highest point of the Cape, and immediately began our work; I and my coxwain, with the instruments; Lieut. Kempe with the boat’s crew raising a pile of stones over the memorial.

At first Diego Ramirez Islands were seen, but before I could get the theodolite fixed and adjusted, the horizon became hazy. At noon satisfactory sets of circum-

At daylight on the 21st we launched and stowed our boat, and set out on our return. We reached the Beagle that afternoon, well laden with fragments of Cape Horn.

Although the South American Pilot spoke of instantly changing weather conditions, we did not believe this until we had experienced it! Twice we witnessed calm conditions change to full gale in less than ten minutes. Several times the wind backed through 90 degrees instantly, with no change of cloud pattern and often visibility would reduce from over thirty miles to half a mile in a matter of seconds. Thus the weather completely dominated our thinking throughout the journey and all decisions were made only after a very careful appraisal of likely meteorological events.

Sandy beaches were few and far between , and steep boulder storm beaches are the best landing places one can expect. Kilometres of cliffs and broken, rocky shores often mean that landing is out of the question. The rainfall is such that almost every bay or beach had a rivulet of drinking water available to us; fresh water and firewood are always to hand. Although there were many areas where the coastlines are cliff-

Cape Horn Island presented a dramatic and awe inspiring spectacle from our stance on the cliffs of Herschel Island. Four miles of angry storm-

Apart from the rapid moving high cloud the sky was clear with the wind blowing about force two. But the swell was enormous, and the rebound effect from the cliffs made for a turbulent sea which pitched our Nordkapp kayaks in all directions and called for very careful paddling. It soon became apparent that to retreat with the sea on our stern quarter would be very difficult and, by a process of non-

At one stage we sought the apparent shelter between a stack and the cliff and were tossed about like matchsticks. With the water temperature at eight degrees centigrade and the waves dumping on the shore in a very terminal manner we knew that a capsize would be very serious indeed. Never had I appreciated the true majesty of the ocean as on this day. As we progressed towards the southern side so we gained a little shelter With the swell running along the face of the cliffs and some respite from the sea. We felt secure enough to take slides and movie, but even as we glimpsed the diminutive beacon which stands on the Horn itself, we knew there could be no relaxing of effort until our feet were back on terra firma.

We rounded the Cape, and another hour and we were in the shelter of the east coast and a sheltered cove on the eastern shore was selected as the landing place and we landed and lay in the sun, but there was bad camping; we put up a fly-

THE TOTORORE VOYAGE 1987

Gerry S Clark and Anthea J Goodwin of Kerikeri, New Zealand and Julia von Meyer of Puerto Muntt, Chile

Abstracted from ‘The Totorore Voyage an Arctic Adventure’ by Gerry Clark 1988

In 1999 Totorore disappeared off the south coast of Antipodes Island, Antarctica, along with Gerry Clark and his crew man Roger Sale.

We were inside the outer rocks, which were quite close to the Cape, and we could see this huge mass sticking up, a high conical shape, cliffs with green on the top, a wonderful setting. Then we could see the tussock up there, and a certain amount of vegetation on the side. There were enormous breakers at the bottom of the dark grey rocky cliffs, and it looked absolutely magnificent! A white lighthouse stood near the bottom of the mountain slope and just to the east of it. As it came abeam with Anthea at the helm, Julia blew three blasts on our foghorn and I reverently dipped our ensign three times in salute to this mighty monument.

About two miles north-

The approaches to the station were a maze of barbed-

Outside, we walked past an emplacement with a small gun like an Oerlikon, all covered up, and then spotted a very surprised man by the door of the cabin. Without a word he bolted inside, no doubt to waken the others; soon two more appeared and greeted us. They asked us to come inside and we stepped into a pleasant little mess room which we found unbearably hot, with a large gas heater turned full on. A large photograph of President Pinochet hung on one wall and a map of Isla Hornos made of wood on another. Various doors opened and more men appeared, rubbing their eyes. The petty officer in charge, in Armada black, was very friendly but obviously put out that we had literally caught them napping. He said we should have radioed that we were coming, as it was very dangerous to cross the barbed-

The next day we sailed into the tiny sheltered cove right next to the station and climbed the steps they had made to the top of the cliff. Anthea came with me to make a more thorough search of the area and we followed the oozy, smelly penguin trails though the tussocks right down to the bottom. It was a large hilly area, full of burrows and very slippery, so it was a relief to walk across a narrow causeway of boulders to a near-

On 28 March we motored around the south-

We wanted to find Sooty shearwater burrows in the stunted coigüe scrub on the sheltered side of the mountain. When we landed in the dinghy, Julia and I found that the boulders on the beach were larger than they had looked from a distance and were very slippery, with deep spaces between. Julia had both her boots full of water before we managed to drag the dinghy clear of the breakers and we realised then that we must always take dry clothes with us in watertight bags. There were Magellanic penguin burrows in the scrub from the shore to about 80 metres up the hill.

On this first day we carried on up the mountainside and had a real struggle in the more dense scrub higher up. From the start it was tough going, what looked like grass swaying in the breeze was actually the tops of rushes which poked through the canopy of dense scrub, which was somewhere between 1.5 and 2.5 metres off the ground itself. Some of the bushes were tangled prickly things, some were tight and cushiony – they were the best to walk on, with the rushes providing handholds. Practice makes perfect, but we never attained that degree of skill and kept tripping and falling. When one disappeared below the canopy it was a painful, time consuming business trying to get back on top, as the branches tangled around arms and legs, sometimes preventing all movement. It seemed an impossible and exhausting task, and progress was extremely slow (one big advantage of snow, we found, was that it levelled out the unevenness of the ground and filled up holes, making it much easier to walk). Far down below we could see Totorore rolling in the swell, and above us, often shrouded in rain, was the jagged peak of Cape Horn. There were no further burrows.

Back on the beach we saw that the sea had got up and the breakers were worse than this morning. It was low tide, and there were more slippery boulders exposed by the receding waves. The dinghy flipped right over with me underneath it and although I managed to grab one oar the other floated out of reach. Holding the boat, both of us fell again on the slippery rocks when the next wave struck. I watched the floating oar, expecting each wave to bring it back in, but it worked its way along the shore, getting further away. How foolish I was not to have had it lashed in the boat! While Julia held the dinghy, I went scrambling over the rocks, trying to keep the oar in view, but it was beginning to get dark and when I last saw it the oar was quite a way out. I dared not paddle downwind after it because it was still in the big waves.

(On another visit to the south-

For a moment I considered remaining on shore but I knew it would be dangerous, as we were both soaked to the skin and night temperatures had been only 1-

The waves partly filled the boat but we managed to get clear of the breakers before a rafaga came. While it was still I could make progress, but could not hold against the wind; I had a welcome rest from the exertion of paddling while Julia held grimly on to some kelp to anchor us. In this manner we progressed towards Totorore. I shouted out to Anthea to put the kettle on, but this proved a bit premature. All was well until we had to leave the kelp to cover the last 50 metres. We almost made it when a great rafaga tore us away toward the open sea. ‘Dear God help us now, give me strength,’ I prayed as I paddled desperately. A very worried Anthea was wondering how to buoy and slip the anchor! I shouted to her to throw us a floating line and she struggled to get one out of the locker, but the wind allowed us to paddle almost within reach again before it whirled us away once more. I could not have continued paddling much longer when Anthea grabbed the end of the oar which I thrust out towards her. A cheap lesson to treat Cape Horn with more respect.

We took it in turns to ‘keep ship’, so that one of us always stayed on board; when weather permitted, the other two continued exploring Isla Hornos. Landings were never easy, but the relaunchings to come back to Totorore were worse. The state of the surf was unpredictable; apart from the obvious lesson about lashing the oars, we learned to take off nearly all our clothes and pack them into watertight containers and bags, wearing just our wet-

On one occasion when I was coming back with Anthea the dinghy flipped over three times. The plastic bags with all our gear were badly holed on the rocks and the contents soaked, so that we had a very large pile of wet gear to deal with when we finally reached Totorore. This became a great problem as we were running out of dry clothes to wear. I lit the cabin heater for the first time since we had left New Zealand, but it did little to dry out the salt-

When we had done all else that we could, there remained only the actual peak of Cape Horn itself. It is only 405 metres high, and the ridge along the eastern cliffs was reasonably easy to follow, after which a steep walk in low but tangled vegetation from the landward side gave access to the peak. It was Anthea’s and Julia’s turn for an expedition, and after a bad landing they took the tent with them and set it up as a base right on the highest point. The weather was kind to them, and from the top they enjoyed glorious views in all directions.

In the evening when they returned they had a very rough time of it on the beach and came back somewhat battered and bruised, as well as soaked. ‘Ah well,’ I thought. ‘That’s that. Now we can leave this place of horrible wet landings.’ I was mistaken. My crew told me that right up on the peak, in tussock grass, they had discovered petrel burrows, and even heard the cooing noise of some sort of petrel in one of them. The news left me excited, determined — and rather afraid. The others were less than enthusiastic, which was understandable under the circumstances, but this is what we had come for and we had to see it through.

It took us all morning, and more, to organise our gear and pack it all up as best we could for a wet landing. Then we had to unpack everything on the beach and stow it into our packs for climbing. It was already 15:30 hours before we finally started upwards. we had to press on hard with our heavy packs, which I found quite exhausting. By the time we reached the saddle above the lake, the cloud had come down around us; we were lucky that we knew the way, and were able to follow yesterday’s tracks. With poor visibility we could find no sheltered place for the tent anywhere close enough to be able to get back from the peak safely in the dark, so we went all the way up.

The wind on top was strong and it was cold, and the swirling cloud around us soaked everything quickly. It was almost dark when we started to erect the tent and completely dark by the time we had finished. Everything we put down had to have a rock on it. With the torch held down by a stone, we struggled with the tent. The pegs were useless as the ground was either soft moss or hard rock, so each corner tab had to have a rock on it, and when we tried to put the rods through, to give it its shape, it billowed out and nearly flew away with us hanging on to it, dangerously close to the edge which dropped away sheer on three sides of us. We almost gave up and considered crawling into the tent flat on the ground. It was becoming serious. We thought of the makers’ claim that the tent had been used on Everest in 100-

Julia crawled inside and tried to get our temporary home a little organised, while I continued piling rocks around the base. Eventually I felt I could do no more and crawled inside too. With one side collapsed from a broken rod, the tent was small inside and flapping wildly, but it soon felt cosy with the hurricane lamp alight and was absolute paradise compared with outside. It was too dangerous to try to light the primus, so we enjoyed a meal of fruit leather, still in perfect condition after a year and a half. We also ate trail bread with sweetened condensed milk, and felt renewed strength. After we had togged up with all the clothes we could get on, we called Anthea on the radio to tell her that we were going outside to look for birds, and then crawled out with the big torch, the hand net and the hurricane lamp, which we dared not leave alight in the tent. Standing still in the wind was difficult as the gusts nearly knocked us over, but once we were wedged into the tussock it was easier. The first two birds I saw briefly in the light were dark, possibly Sooty shearwaters, but after that they were small, white underneath and blue on top, obviously prions or Blue petrels. This was what we had come for.

We searched the little passages between the tussocks and the entrances to the burrows, hoping to find a bird sitting quietly waiting to be picked up. But the main entrances were over the edge and it was dangerous in the very strong wind. Several times Julia cried out, ‘Cuidado! Look behind you, there is nothing there!’ Shining the torch down into the nothingness, we clung tighter to the friendly tussocks. We stayed out for two hours and it was 22:30 hours when we crawled back into our haven in the wildly flapping tent. Everything was damp but inside our sleeping bags with our clothes on we soon felt warm again. The ground below was very cold and Julia insisted that I should use the polyurethane roll, as we only had one. Julia managed to sleep quite well — I heard gentle snores from the depths of her bag -

For two days we were stormbound in cove Cabo de Hornos, and could not go ashore. While waiting, we speculated on the birds up on the peak. The weather was still discouraging when Anthea and I climbed back up Cape Horn mountain to set up camp again. The air temperature was only just above freezing and there were some nasty rain squalls, but we felt that we could not wait forever. The new camp site was much better and more sheltered than on the peak itself, and we trod down some scrub to make an insulating layer under the tent. Loosening rocks to anchor the tent and fly was troublesome, but eventually we felt it was secure enough to leave it while we went up on the peak. Having donned extra Damart underwear, sweaters, scarves, and gloves, we set off once more to face the top of Cape Horn, carrying a piece of bamboo and a boat hook to use as poles for our mist net, in which we hoped to catch a petrel, and finding them very useful as staves for support against the sleet-

It was midnight when we crawled into our sleeping bags, complete with our goros (woolly hats), and lay down to sleep listening to the Blue petrels calling with their delightfully soft voices as they flew around the mountain. ‘Dear little things,’ murmured Anthea as she dozed off.

It took two trips to get all our gear back down to the beach, and on the way we investigated several other clumps of tussock and found many more burrows with Blue-

Anthea Goodwin one third way up the eastern side of Cape Horn southern cliff. The original lighthouse can be seen in the far distance

A combination of experience, advice from the Chilean Navy and, as in all such ventures, luck had helped us round. We buttoned up our anoraks and set out to explore Cape Horn.

Next day was a rest day and we climbed to the top of the 400 metre high Horn. It was very hard going in either dense vegetation or bog. The wind indicator jammed at maximum -

The Horn itself was impressive, but I didn't feel any particular elation when we finally realized we had achieved our objective. The climb to the top left a lasting impression for two reasons: firstly because the terrain was such difficult going that I was completely shattered. Barry, who was a Himalayan mountaineer remarked during the climb that it was the hardest low-

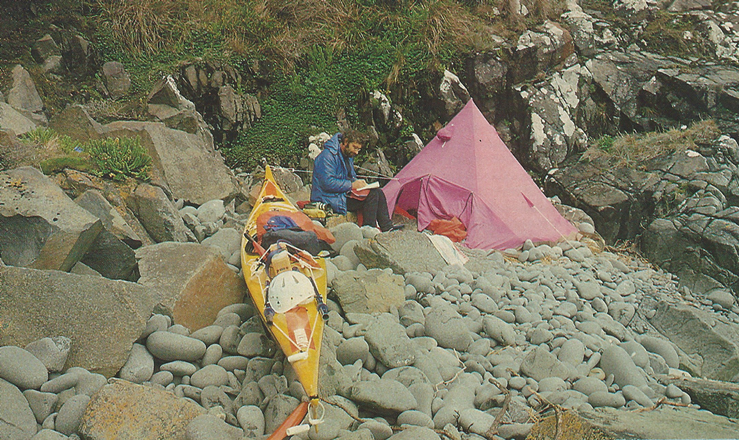

Frank Goodman at the bivouac on the boulder beach to the east of the southern cliff of Cape Horn

AN ASCENT OF CAPE HORN 1928

Francis K Pease

Abstracted from ‘To The Ends of the Earth’ 1935

ONE of our trips, away to the westward of South Georgia, ended with our having to put in to Cape Horn for shelter. Shelter at Cape Horn — that most notorious of stormy capes! It certainly sounded like seeking hospitality in the very home of the inhospitable! But there was nothing else for it. The weather was terrible — Cape Horn weather at its worst. In the midst of the great rolling welter of the sea our little William Scoresby was as nothing. We were swept again and again. It was weather that a vessel ten times our size would have had no business to be in. Oh, but a fine brave craft was our little William Scoresby!

With consummate skill the Captain kept her up to the seas. A small craft in a big seaway — that is when it is revealed whether a commander is a real seaman. Hour after hour they kept the vessel heading up to the tremendous seas, but at last it was evident there was nothing for it but to make for shelter. We were losing ground, drifting back in spite of the engines being kept full speed ahead. The order was given and we wore round and headed in for where the charts said a shallow anchorage existed just round the corner of the Cape, on the Atlantic side.

The wind and seas were from the Pacific side, which meant that the Atlantic side was sheltered; but great caution was necessary all the same. We had to feel our way into the harbour. It was imperfectly charted; the depths marked on the chart were few and far between. We had to sound continually. Here the water was smooth enough, but all about us were jagged rocks. Sometimes there was only just enough water for us to clear them. Sometimes we were compelled to stop, while an officer and some of the men went ahead in a boat and took a line of soundings only a few feet apart.

And all the while from the Pacific side of the Cape, from just round the corner, came the thunder of the tremendous seas. It was as if, enraged at our escaping them, the mighty rollers were trying to batter down the protecting barrier of land between us. At last, however, we came into the little harbour proper, and anchored; and there for some days we lay, waiting for the storm to abate, which, as is the manner of Cape Horn storms, it was in no hurry to do.

One day a party of us made an expedition ashore. Our object was to try and ascend the steep slopes of the Atlantic side of the coast and come down on the Pacific side—-

We landed on a part of the beach near where stood a tall finger-

We followed the direction of the finger-

On the wooden walls were numerous initials — obviously cut with the points of sheath knives — and penciled inscriptions. The inscriptions were in a great variety of languages, including even Chinese and Japanese. Many were so faded as to be unreadable, but with others we managed to make out the words. One of the English ones was: “Thank God for this place” -

From the wreck-

Nor was this all. Much of this vegetation grew horizontally out from the rock face — shrubs; great trees; bushes all tangled with vines. We stood on the horizontal trunks of trees, and above us and all about us, sticking straight out, were the trunks of other horizontal trees. It was a topsy-

Up and up we made our laborious way, resting frequently in order to get our breaths. During one of these halts a scientist member of the party discovered copper-

As we went on, the tunnels through the undergrowth became more frequent; indeed, most times our only way of ascent was up through them. Once we encountered opposition — a bird, large almost as an albatross, that came flapping down the tunnel. So big was he that he nearly filled it. He screeched as he saw us, no doubt as surprised to see us as we were to see him; and we threw ourselves down flat so as to dodge the swooping of his wings. When finally he had scraped past and it was found that none of us had been injured we were thankful indeed.

Other fauna that we encountered were monstrous wild cats. When I say “monstrous” I mean it. They were six times bigger than ordinary cats, and terribly vicious. They looked like small leopards. There was a rifle or two among us — small, .22 calibre weapons — and whenever one of these cats was seen he was fired at. Because of the thickness of the foliage, aiming was difficult, but some of the shots went home none the less. The results in each case were startling. Wounded, the cats became fair devils, and returned the attack. There was one that came leaping towards us with a swaying, swerving motion like that of an African leopard. It spat hate, and screamed it, filling the eerie jungle with sound. You’d have thought there were a score of the animals, not merely one. There was a sigh of relief when at last with a lucky shot somebody killed it. Another of these wounded cats came dropping down from directly above us. The first part of its drop was down through a lot of very thick leaves, and we lost sight of it for a moment. Then it appeared on a bough only a few feet up. There for an instant it stood crouching, then, screaming, it dropped and landed on the shoulder of one of our party.

Its objective was the man’s throat, and, digging its claws into the man’s shoulder, he strove to get at it. It was a fine old commotion; the man fought back, tore at it with his bare hands; the cat squealed, dug its claws still further, and snapped. Its movement were almost unbelievably quick, and the affair might have ended very badly for the man if another member of the party -

We now began to come across traces of human beings — the strange Patagonian primitives. In the face of the rock we found caves, usually with tunnels through the undergrowth leading to them. In the caves were ashes of cooking fires, and food debris — the skins of birds whose bodies had been eaten. In some places we found footprints of these people. In one cave the ashes were scarcely cold -

In spite of our endeavours, we did not succeed in getting over to the Pacific side of the Cape after all. By the time we reached the top the day was so far advanced that night would have been upon us long before we could reach the bottom of the Pacific side; and after that there would be the long tramp back round the shore to our anchorage. A break in the vegetation gave us a view right out over the sea — the sea on either side of Cape Horn, the mountainous rollers of the Pacific side, the comparative calmness of the immediate Atlantic side, while before us were the rolling wastes of the south. Directly below us was the harbour, with the William Scoresby looking like a toy, and a not very efficient toy at that. And, just rounding the Horn was a big top-

We decided to go back the way we had come, the way we knew; and this we did, dropping down through those queer tunnels and from one horizontal tree to another, almost like so many monkeys, and reached the ship, glad indeed to be back in an environment where objects were right way up.

Stunted Southern Beech entanglement Cape Horn Island

The rock of Cape Horn itself is a grey diorite, which resembles granite except that it has smaller crystals; called by Darwin 'Greenstone'. It contains felspar, hornblende and mica. Our most interesting discovery was that the cliff of Cape Horn is in fact one face of an arrete, and nestling within yards of the Southern Ocean is a small corrie lake tucked into the eastern shoulder of the peak, yet completely invisible from the sea and although it was not an original discovery, it was so unexpected, that in many ways it was the most satisfying discovery of the journey.

The climate had hammered the vegetation into submission. Much of the land surface was covered in bog -

The most common plant is the evergreen southern beech tree, Nothofagus Betuloides. Sheltered from the wind, this tree grows to a height of sixty feet or more, but exposure can reduce it to a shrub just a few inches high. Much of the bog confined to sheltered spots was interspersed with areas of beech trees reduced to scrub, growing to a height of approximately three feet. They were too dense to push trough and just not dense enough to walk on top of -

A bright orange fungus Cyttaria Darwinii grows on the beech trees. The brightly coloured sphere, the size of a small orange are instantly recognisable from the description given in Darwin's 'The Voyage of the Beagle'; these are edible, and I found them pleasant to chew, but tasteless. The only other edible plant we found was wild celery. Although we fished on occasion we never caught anything! We did find plenty of mussels to eat, and also a delicious limpet, called Lapas by the Chileans. It is approximately three inches across the base and has a 3mm diameter hole at its apex and is easily prised off the rocks at low water.

On some of the drier, exposed bogs of the Island fingers of beech scrub penetrated the bogs along the line of the prevailing wind. We discovered these were effective booby traps, as the beech only rose above the bog surface by a few inches, but actually grew in a trough several feet deep. We fell in! Although the general mechanism of this association was clear to us, we couldn't decide whether the beech fingers had encroached into the bog or whether the reverse was true. None of us had ever seen this sort of trenching anywhere else. It reminded me of some deserts where the ridges lie parallel to the prevailing wind. Since our return I have asked various experts on bogs about this interesting association, but no one has ever seen anything comparable elsewhere. It may be unique to Cape Horn Island.

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Nigel Matthews, Jim Hargreaves and Barry Smith in the shelter of the bay to the east of the great southern cliff, having rounded the Horn. The route to the summit can be seen behind them.

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Chilean Armada post -

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Frank Goodman on the ascent

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Tussock Grass in sheltered spots can grow to 2 mt and provide a substantial obstacle

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Barry Smith on the summit of the great southern cliff. Looking east

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Barry Smith and Frank Goodman placing a message in a bottle in the remains of the summit cairn

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

The message in the bottle in the remains of the summit cairn, they have received no replies

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn

Frank Goodman taking a 360 degree 8mm cine film on the summit. Looking west -

Copyright the British Kayak Expedition to Cape Horn